Banning Eyre on Bringing African Music into the American Music Scene

Text by Dawoud Kringle

On Thursday, July 15th, 2021, MFM presented its fifth webinar in the Music is Essential series. This one featured Banning Eyre, and the discussion centered around bringing African music into the American music scene.

On Thursday, July 15th, 2021, MFM presented its fifth webinar in the Music is Essential series. This one featured Banning Eyre, and the discussion centered around bringing African music into the American music scene.

MFM advisory committee member Banning Eyre is an author, guitarist, photographer, and Senior Producer for the Peabody Award-winning public radio series Afropop Worldwide. Traveled to some 25 African countries researching music for the Peabody Award-winning public radio series Afropop Worldwide, and studied traditional guitar styles in a number of African countries.

Eyre has produced over 180 Afropop episodes including in-depth coverage of Mali, Congo, Egypt, Ghana, Lebanon, Madagascar and Nigeria. He comments on world music for NPR’s All Things Considered.

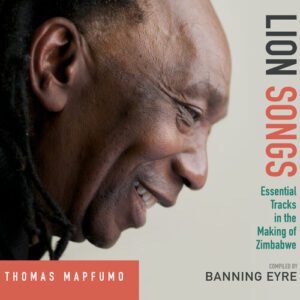

In May, 2015, Duke University Press published his fourth book, Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Music That Made Zimbabwe, which won the 2016 Society for Ethnomusicology African Music Section Kwabena Nketia Book Prize. His previous books are Afropop! An Illustrated Guide, In Griot Time: An American Guitarist in Mali, and Guitar Atlas Africa, a book of introductory lessons in African guitar styles.

In May, 2015, Duke University Press published his fourth book, Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Music That Made Zimbabwe, which won the 2016 Society for Ethnomusicology African Music Section Kwabena Nketia Book Prize. His previous books are Afropop! An Illustrated Guide, In Griot Time: An American Guitarist in Mali, and Guitar Atlas Africa, a book of introductory lessons in African guitar styles.

He also co-produced the 2004 film Festival In the Desert: The Tent Sessions, filmed in location in Essakane, Mali. He runs Lion Songs Records, an independent label.

The webinar was hosted / moderated by MFM member Adam Reifsteck.

Reifsteck opened the webinar and introduced Eyre. Eyre began by describing his work with Afropop Worldwide. He started the project with Shawn Barlow in the 70s. He’d begun with classical guitar, and was at first unfamiliar with African music. Barlow’s travels to Africa began their in-depth understanding of African Music. Funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting allowed them to start their radio show.

Banning Eyre went over the history of Afropop, showing a series of photos, audio, and video clips which told the story of their evolution. The scope of this history is too long and nuanced to present in this brief report. Suffice it to say that Eyre’s participation in the introduction of African music to the US proved of incalculable value.

It’s well worth the effort to watch the video of the webinar (https://vimeo.com/576038680/7f2bf854a1). The history he presented is amazing.

Eyre ended his presentation by playing some Malian style guitar, with the second piece based on an mbira composition. It was beautiful and fascinating. Any guitarist would find something to learn from examining his technique. One thing he pointed out (which will be noticed in the video) is the interplay between 4/4 and 6/8 time. This music seamlessly allows the two time signatures to flow together. He concluded by saying that mbira songs never really end; you just join in for a while.

The webinar was then opened up to questions from the participants.

Dave Liebman (MFM advisory committee member) offered the first question. He was curious if Eyre had any experience working with Mauritanian singer Dimi Mint Abba. Eyre had no direct experience with her. He did mention Dimi’s daughter (or relative) Mora Mint Samali.

Sohrab Sadaat Ladjavardi (MFM President) introduced record producer Verna Gillis, who’d joined the webinar. She received greetings from several participants (her reputation and acquaintance preceding her). Gillis’ work as a producer and ethnomusicologist made her presence a welcome addition.

Liebman interjected with a question of whether anyone jumped on stage with any of these groups and sat in with a horn. Eyre replied that things like that have happened. He also described his own experiences sitting in as “nerve wracking.” He particularly remembered how difficult it was playing with Thomas Mapfumo, who was a perfectionist with his music.

Roger Blanc (MFM board of directors) asked Eyre about rhythms; specifically the subdivisions of 12/8 time which he heard in this music. Eyre replied that Blanc’s assessment of these rhythms are essentially correct. But African musicians (with the possible exception of some of the younger ones) do not think in those terms. He also touched upon how musicians from different parts of Africa would approach this differently. Blanc drew a parallel between this and what the Grateful Dead did.

Eyre mentioned that one of the things that attracts him about this music is its immediacy, and the fact that it cannot be played half-heartedly. There is nothing casual about it; yet it is not forced.

There was also discussion about the musical conversation between Africa and the Americas. It has actually been going on for longer than one might imagine. This conversation has been two sided for centuries.

Blanc brought up the major influence of African music in the form of a rhythm section. Traditional European classical / art music didn’t really have this. The presence and reliance of a rhythm section being of African origin. Eyre expanded on this complex interconnection.

Sohrab shared something regarding his experience with African musicians he’d played with, such as with Salif Keita. Regardless of where they are from, they don’t look at him in terms of his race, religion, nationality, etc. They simply said “let’s play” and accepted him as he is. He shared that when he asked Salif Keita why he accepted him, and Keita said “You are big. You have what we like about musicians.” This got a laugh from everyone. But it was the openness to accept him – or anyone – for who they are that separated the attitude of African musicians from other musicians.

Eyre expanded on the openness and sense of community that is woven into the mindset of African musicians. One exception Eyre experienced was in Zimbabwe. There were a lot of racial tensions there, mainly owing to their unstable political situation (and undoubtedly their unworkable and disastrous economic system). When he played there with Mapfumo, the first thing people would ask him was “when are you leaving?” But once they actually heard the music he played, they accepted him.

On this note, the webinar concluded. Some mention was made of a possible part two of this webinar. This may be inevitable; the subject of African music is simply too big to cover in one hour.

Ultimately, this webinar that MFM presented showed that all of the differences among humanity only point out our similarities. We only have to look for common ground, and build from there.