Date: Tuesday, September 24th, 2019

Date: Tuesday, September 24th, 2019

Venue: WingSpan Arts (NY)

Review by Dawoud Kringle

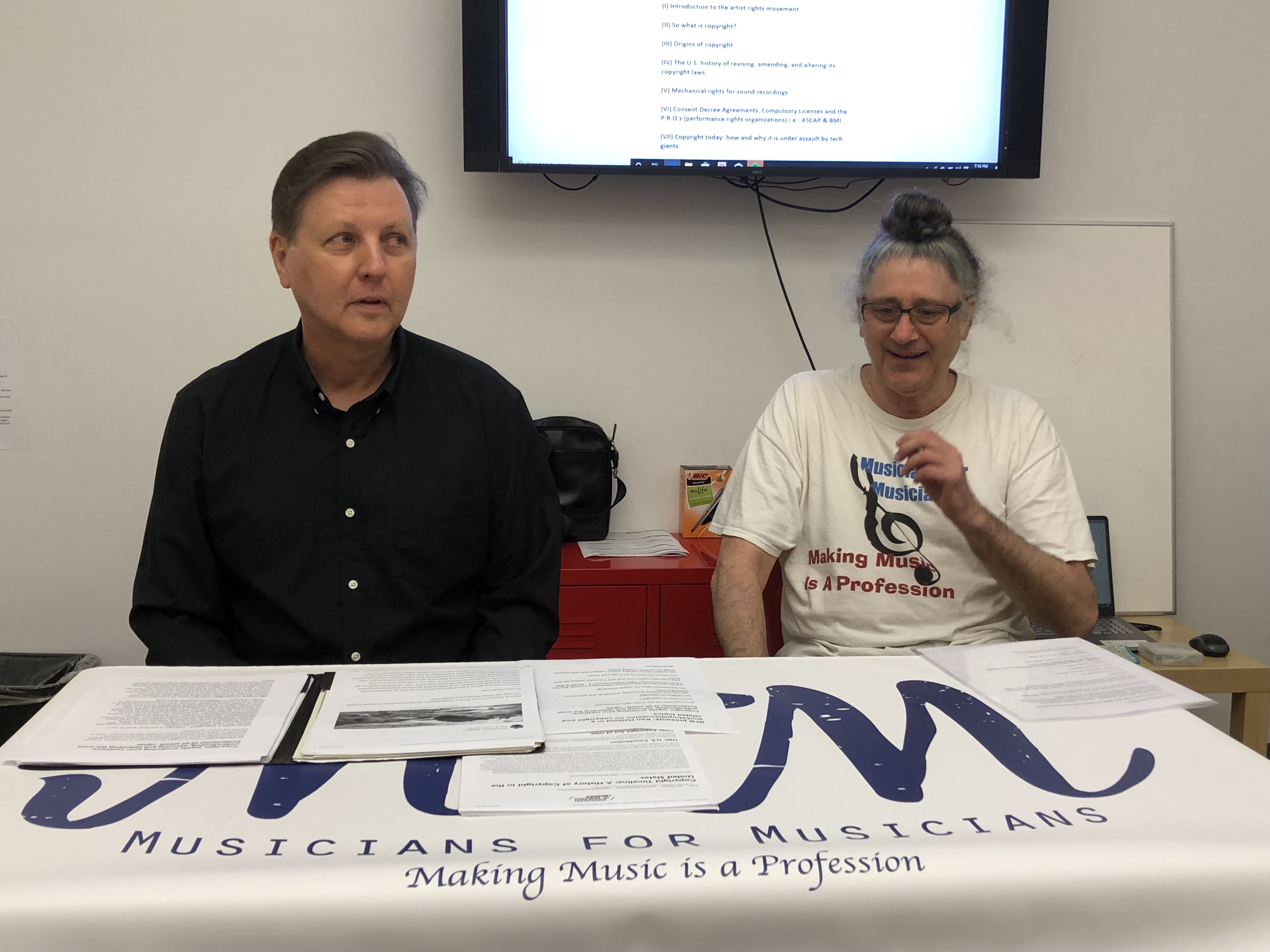

On Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, Musicians for Musicians (MFM) presented a milestone in its Workshop Series: Workshop with Ken Hatfield Speaking about Copyright – legally protecting your creations.

MFM Members and friends are no stranger to Ken Hatfield. Described as “a veritable Picasso of the jazz guitar world” (20th Century Guitar), and “one of the most skilled, creative, and original guitarist/composers currently recording” (Acoustic Guitar), Hatfield is a master guitarist, composer, recording artist and band leader with 10 CDs as a leader to his credit, Hatfield is also a leading artist rights activist. He serves as co-chair of the Artist Rights Caucus (ARC) of Local 802 and as a member of the Advisory Committee of MFM. In April 2019 he participated in the United States Copyright Office’s fifth and final round table on reform of section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

Hatfield’s immense knowledge about the intricacies and nuances of the music business make him exceptionally qualified to lead this workshop.

Sohrab Saadat Ladjavardi opened the workshop with an introduction to Hatfield’s qualifications, and quoting Hatfield’s own words describing why he is a musician’s rights activist. Hatfield began by describing the ongoing struggle between those who create music and those who profit from the labors and creations of others.

Copyright is the legal right to make copies. Copyright is the extension of property rights. The ownership of tangible, physical property is easy to prove, and society has devised legal methods of identifying ownership. With something as ephemeral and intangible as a musical composition or intellectual property, proof of ownership becomes more difficult. Copyright provides this method of proof.

Hatfield offered a brief yet comprehensive view of the history of copyright law. The beginning can be traced to 1436, with the invention of movable type and printing press. Within 50 years, the number of books in Europe increased from a few thousand to 10 million, necessitating the legal means of identifying ownership of the intellectual property of the authors. In 1710, the first copyright law was passed that introduced the idea that the author of a work was its legal owner. The first copyright law in the US was passed in 1790.

The problem was that every country had very different copyright laws. There was no uniformity of copyrights. Successful efforts to rectify this were attempted in 1886; with the US joining this in 1988. Legally, a work is copyrighted the moment it’s created and documented in some manner. The SR (Sound Recording) option was instituted in 1976; a copyright applicant could send in a written score, you could send a recording. In 2005, there was a Congressional Request for the study of the history of copyrights, because they wanted to understand how to deal with “orphan works” (works that one cannot find their legal owners). Hatfield continued to go into considerable detail about the history of the evolution of copyright law. He went on to describe other milestones in the evolution of copyright laws, such as the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), which was met with opposition after it was passed), and the recent Music Modernization Act (MMA).

In our lifetime, we are witnessing the greatest expansion of technological knowledge in human history. Consequently, more secure copyright is necessary to protect the legal ownership of the individual’s creations – despite what Big Tech wants you to believe.

Hatfield pointed out that there are a lot of common misconceptions about the copyright laws in our country. He described the actual process of trying to get a law passed (I refer the reader to past articles here and in DBDBD documenting the passing of the Music Modernization Act). There are also the inevitable changes in technology and consumer habits and tastes. These factors necessitate approaching copyright laws as a constant work in progress.

Hatfield spoke about some of the “Safe Harbors” that were created to protect providers like YouTube, Google, etc. This way, YouTube, or whoever, would have very limited liability for what content creators did with copyrighted material. Thus, if X violates Y’s copyrighted material, the provider cannot be sued for this violation. The situation is complicated by the fact that copyright is a federal law, and must be tried in federal court. Court costs can run from $375,000 to $1,000,000, and lawyer fees are determined at the sole discretion of the presiding judge (not to mention the case can be tied up for years with remands, appeals, etc.). In the meantime, YouTube can still carry the disputed song / content, attach advertising to it, and collect revenues while the case is being fought.

Hatfield went on to discuss mechanical rights for sound recordings, Consent Decree Agreements, Compulsory Licenses and performance rights organizations (PROs, such as ASCAP & BMI). A mechanical license is an agreement between a music user and the owner of the copyright, which grants permission to release a song in an audio format. This is different from a copyright. It is the mechanical license that, among other things, puts limits on the use of samples of songs, and mandates that the original copyright owner be paid of someone makes use of the copyrighted material. The practical details of Synchronization Licenses (an agreement between a music user and the owner of a copyrighted composition that grants permission to release the song in a video format) and Consent Decree Agreements (a settlement decreed by a judge based on an agreement signed by two parties who’d agreed to accept the judge’s decision without knowing in advance what it would be) were also discussed.

Another main topic of discussion was how and why copyrights are under assault by tech giants. Inevitably, the insane payment system for online streaming services came up, as well as the underhanded practices of the large corporations to devalue music came up.

Actions we can all take and / or support that will improve the situation for content creating artists, and what artists need to do to get paid were also brought up. Hatfield stressed the importance of registering one’s works with the copyright office (a registration application, copies of the work, and the application fee). The reader can get the forms here: https://www.copyright.gov/forms/. Copyright registration creates a public record of your registration. Among other things, this helps people who wish to license your work, to ascertain the status of your work, and to find you so they can pay you for use of your work.

The next thing that must be done is to make sure that any digital file of your work has an International Standard Recording Code (ISRC). This is a unique identification system for sound recordings and music video recordings. Each ISRC code identifies a specific unique recording and can be permanently encoded into a product as a kind of digital fingerprint. There are several online companies that exist that provide this service.

It is beyond the scope of this article to encompass the extensive and comprehensive body of knowledge Hatfield presented in the workshop. His presentation was saturated with detailed and nuanced instruction, all of which is indispensable to the professional (or aspiring professional) musician. The most important thing to take away from this is that it’s up to the musicians to take control of their own business affairs, and make sure we are paid our rightful share of the money our work is generating. To quote Hatfield “If you created it, you should be getting a healthy taste. And if you’re not, somebody’s taking advantage of you”

Note: you can watch the whole workshop on video on the Member Portal.